Los Angeles, California

Lynch / Eisinger / Design uses a series of new outdoor spaces to recast an industrial relic into a cool (and green) place to work.

By Clifford A. Pearson-via:archrecord

Photo © Amy Barkow/Barkow Photo

Using a process of renovation through subtraction, the New York—based firm Lynch / Eisinger / Design (L/E/D) created a multitenant commercial building in part by taking away pieces of an old industrial complex. But its scheme respected the integrity of the remaining buildings and, indeed, leveraged their muscular structure to give character to the new facility.

Program

Set in the Culver City area near many of Eric Owen Moss’s projects, 3641 Holdrege Avenue joins a number of buildings in this part of town converting from industrial to commercial use. The project’s developer, Urban Offerings, saw an opportunity to serve an emerging market of creative businesses such as technology start-ups and design-related companies. The developer hired L/E/D because it had experience creating showrooms and retail space for design and fashion companies. The firm also shared the developer’s commitment to sustainable design.

Solution

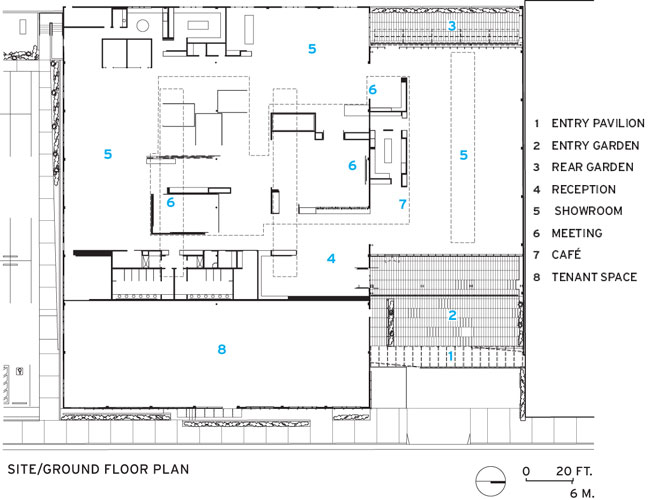

Given a trio of industrial buildings that had served as a diaper factory, and then a clothing warehouse, the architects — Christian Lynch, AIA, and Simon Eisinger — realized early in the process that less would be more. So they tore down a generic shed dating from the 1980s on the south end of the site to provide surface parking. And they sliced off pieces of a second building to create a pair of courtyards — one in front and one in back — that bring daylight into the structure.

But they restored the remaining buildings, dating from 1956, which stole their hearts with hard-working bowstring-truss roofs and tilt-up-concrete envelopes. “We all fell in love with the wood roof structures,” recalls Dean Nucich, managing principal of Urban Offerings. “The bowstring trusses and curved plank-roof decking are classic mid-century L.A.,” states Eisinger. So they sandblasted the trusses and the concrete to reveal the warmth of the wood and the rugged quality of the walls and floors.

They also tore out five decades of accretions, such as interior partitions, ceilings, and finishes. “We wanted to show that the original materials are beautiful,” explains Lynch. They also restored two long skylights and existing windows, but installed high-performance glazing to reduce energy consumption, and added light scoops to bring daylight into the 28,500-square-foot building.

To upgrade the existing structures’ seismic performance, the architects added steel clips and panels securing the connections between the tilt-up concrete walls and the wood trusses.

For the project’s lead tenant, a showroom and national sales center for Herman Miller, Lynch and Eisinger gave the northern portion of the complex its own dramatic entry sequence. Facing the street but recessed from it, a slatted-Douglas-fir and Cor-Ten-steel pavilion grabs attention while offering only glimpses of what lies beyond. Visitors walk through the pavilion, which has no doors, to get to one of the courtyards carved from the old building. At night, a Cor-Ten gate that had been tucked flush with the back wall of the pavilion, swings out to close off access to the courtyard. The roundabout route helps visitors shift their minds from hectic city thoughts to quieter garden musings, says Lynch.

Where they had sliced the old building, the architects inserted new steel moment frames — in front and back — and glass curtain walls to help light the spacious interior. To shade the glass wall on the east, facing the larger courtyard, they suspended a slatted-wood screen from above. On the west, they protected the glass with steel grating that projects out from the building like a pergola.

Where they had sliced the old building, the architects inserted new steel moment frames — in front and back — and glass curtain walls to help light the spacious interior. To shade the glass wall on the east, facing the larger courtyard, they suspended a slatted-wood screen from above. On the west, they protected the glass with steel grating that projects out from the building like a pergola.

Although they didn’t design the interiors, Lynch and Eisinger created an architectural setting that establishes a strong relationship between indoors and out and leaves a strong imprint on the spaces inside. They landscaped both gardens with native species that do not require irrigation and used a Minimalist’s aesthetic that ties the outdoor spaces to a long line of Modern design. In the front courtyard, they planted a palo verde tree, which “populates the space at all times,” says Eisinger.

On the southern portion of the complex where two tenants recently moved in, the architects wrapped the upper portion of the building with Cor-Ten panels and extended them above the structure to reduce glare from the roof’s white surface. Lynch and Eisinger used the white roofing to reduce solar loads inside, which along with other shading strategies and material selections earned the project a LEED Gold rating.

Commentary

Working with a tight $3 million budget and a limited palette of materials, L/E/D gave a forlorn set of buildings a new identity as a hip place to work or shop for good design. The project’s intriguing entry sequence, which teases visitors inside, shows that sometimes the best way is not the most direct way. It also demonstrates the power of spaces that flow gracefully from outdoors to inside.

Completion Date: December 2009

Gross square footage: 31,500 sq. ft. (including courtyards)

Total construction cost: $3 million

Owner: Urban Offerings Inc.

Architect:

Lynch / Eisinger / Design

224 Centre Street, 4th Flr. NYC, NY 10013

212.219.6377

212.219.6378

www.lyncheisingerdesign.com

Gross square footage: 31,500 sq. ft. (including courtyards)

Total construction cost: $3 million

Owner: Urban Offerings Inc.

Architect:

Lynch / Eisinger / Design

224 Centre Street, 4th Flr. NYC, NY 10013

212.219.6377

212.219.6378

www.lyncheisingerdesign.com