Gus Wüstemann

Post By:Kitticoon Poopong

Photo © Bruno Helbling

The living and sleeping areas are surfaced with new oak flooring and wainscoting that conceal radiators and lighting. The ceiling and remaining walls expose the original materials and historic finishes, such as the patch of fresco behind the dining table.

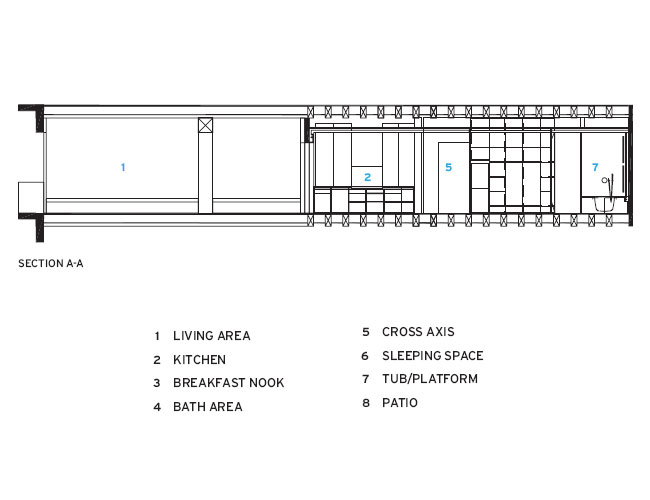

A backlit panel of translucent glass-fiber-reinforced polyester resin surrounds the entrance to the sleek, white cross axis that forms the functional heart of the apartment and separates the restored front and back sections into public and private spaces.

Wüstemann commutes weekly between his practice in Zurich and Barcelona, where he has settled with his wife and two children in a 2,000-square-foot apartment in the heart of the Gothic Quarter. Baptized the Crusch Alba (“White Cross” in Romantsch, one of Switzerland’s official languages), this residence demonstrates just what Wüstemann means by deprogrammed architecture.

Softly illuminated cove lighting lines the perimeters of the walls and ceilings throughout the old and new spaces in the apartment, uniting them visually and imparting the illusion of an endless horizon.

The apartment, situated on the second floor of a building dating to about 1860, is divided by a major bearing wall. The existing front half, with three floor-to-ceiling balcony windows overlooking a narrow pedestrian street, easily lent itself to becoming an open living area. But the back was a warren of rooms dimly lit by several tiny patios. After studying dozens of possible solutions, Wüstemann came up with the idea of the white cross. Inspired by the notion of an urban crossroads, he enveloped this cross in white gypsum board and subtle lighting to create an organizational center that fills the rear section with abundant light.

Photo © Bruno Helbling

Appliances and kitchen storage, as well as bath fixtures and fittings, are discreetly hidden behind doors and under hinged sections of counter to maintain the aura of Wüstemann’s deprogrammed architecture.

Superimposed over the existing structural shell of the building, which Wüstemann stripped, patched, and varnished, the cross is defined by the planes of its ceiling and white epoxy floor (with radiant heating coils below), and by the running strip of cove lighting that snakes around its edges and beyond. The overall effect is a rich sense of spatial layering in a limited area.The linear continuum of indirect light is fundamental to Wüstemann’s concept. “[It] suggests depth and a horizon,” he explains. “There is no end to the space; it doesn’t stop. You will never see a light source in my projects, because there’s no horizon.” To emphasize the importance of this detail, he always keeps this discreet illumination turned on, but often dimmed.

Photo © Bruno Helbling

A breakfast nook, adjacent to the kitchen, is tucked into a small space created by the formation of the central white cross.

Taking advantage of the new floor plan, Wüstemann tucked a breakfast nook and sleeping alcoves into the spaces that formed around the geometry of the cross. Then he created a kitchen along the axis adjacent to the living area, and a bath corridor across that, keeping all of the fixtures, fittings, and appliances hidden in cabinets when not in use. A section of counter lifts up to reveal a six-burner gas cooktop, and pocket doors open and fold back into the cabinetry when it’s time to access the refrigerator, freezer, oven, microwave, and storage. The architect also installed two lavatories behind a sliding door on the right arm of the bath axis. He housed the toilet in a cubicle, and a windowed shower nook at the far end. In the opposite direction, the left arm of the cross opens onto the master bedroom area.

Photo © Bruno Helbling

The cove lighting continues back around the walls of the master bedroom — accessible from the left horizontal arm of the cross axis — supplementing the daylight that filters into the room from the adjacent patio window.

The family can move various sliding and folding doors to define up to three bedrooms and isolate the bath corridor, but they prefer to keep them open. “The kids have foldable mattresses, so they can choose where they want to sleep,” says Wüstemann. “They are ‘camping’ in the apartment.” One of their favorite places is a raised surface off the kitchen, near the master bedroom, where a bathtub is hidden under removable panels

The family bathtub has a hinged, glass-fiber-reinforced polyester-resin partition and is covered with removable panels. When not in use, it doubles as a sleeping platform for the architect’s children — who love to "camp out" around the loft on their foldable mattresses.

This concept of loose, flexible living extends to the front of the apartment, where Wüstemann installed new oak floors to define a habitable platform within the shell of the old structure. This expanse of wood continues up the walls to form a low wainscoting backed by a recess that accommodates runs of discreetly hidden fluorescent lights and radiators. The walls, like the ceilings with their exposed beams and typical Catalan rafters and vaulting, are stripped to the original materials — wood, brick, stone, and plaster — and coated with a semigloss varnish to minimize dust and enhance the daylight filtering through the windows. During the renovation, Wüstemann added steel beams to reinforce the ceiling and allowed the scraps and bits of different finishes and interventions to emerge. This includes the salvaged remnants of a plaster fresco, located behind the dining table.

Wüstemann’s scheme is guided by a metaphor of urban space. In an earlier Lucerne loft, he used the idea of a glacier to create an interior “landscape” of ascending levels and descending light [record, September 2007, page 129]. Here, the unfinished walls, marked with time, are extensions of the Gothic Quarter, and the white cross and living platform are elements the family can appropriate freely. “It’s the aura of not finishing, keeping it urban and letting the process be visible that gives a feeling of freedom,” he says. This interpretation of domesticity as an improvised encampment amid historic remains offers an interesting insight into the life of a modern urban nomad, in which a family can commute between two different worlds and feel at home in both.

The people

Architect(s): Gus Wüstemann

Location: Barcelona, Spain

Photographs: courtesy of Gus Wüstemann

Completion Date: April 2009

Gross square footage: 2,000 sq.ft.

Total construction cost: €;300,000.000

Gus Wüstemann ma eth sia coac

architects@guswustemann.comwww.guswustemann.com

Albulastrasse 34, 8048 Zürich, Switzerland

T/F +41 400 20 15/17

C/Banys Nous 15, Ppal 2, 08002 Barcelona, Spain

T +34 93 393 61 75

via:archrecord--By David C