Kengo Kuma & Associates

Post By:Kitticoon Poopong

|

| Photo © Courtesy of Shinkenchiku-Sha--Kuma placed the main entrance at the south end of the building, which visitors reach after walking along a 148-foot-long path. |

With a new name, a new logo, and a new building, the Nezu Museum has transformed itself from a staid cultural institution into Tokyo’s latest “it” destination. Despite a world-class collection of Asian antiquities and a central location in the city’s fashionable Omotesando district, the old museum (the Nezu Institute of Fine Arts) and its traditional garden kept a fairly low profile. But thanks to the new building and landscape design by Kengo Kuma, the Nezu is impossible to miss. Topped with a dramatic tile roof, Kuma’s building stands apart from its commercial surroundings. Yet it greets pedestrians warmly with a live bamboo wall symbolizing the elegant blend of architecture and nature inside.

|

| Photo © Courtesy of Shinkenchiku-Sha--A pitched roof with ceramic tiles connects the building to Japanese tradition, but tapered, steel eaves give a modern edge to the design. |

Removing the storehouses enabled Kuma to reposition the museum’s entrance more prominently—to the end of Omotesando’s famous, boutique-lined street (instead of a sequestered approach from Kotto Dori). A 148-foot-long walkway leads to the building’s main door, in the process taking visitors away from the buzz of the city. Inside, an intimate reception area adjoins an expansive sculpture hall overlooking the 161,459-square-foot garden. From the hall, visitors can either go outside or enter the six galleries: three on the ground floor and three (plus a lounge) on the second floor—all accessed by a glass- and-steel stair in the middle of the room. While a café occupies its own Kuma-designed garden pavilion, a shop sits near the museum entrance.

A second stair descends below grade to a 70-seat lecture room, and a hidden corridor behind the galleries connects to the old wing.

Though the new Nezu has more gallery space, its administrators’ primary goal was to improve the quality of the exhibition area—in terms of both conservation and display. Because of their fragility, most of the artifacts make only brief appearances in the galleries, each one designated for a different medium, such as decorative arts, tea ceremony objects, or calligraphy. Sequestered behind solid, steel-reinforced-concrete walls, the galleries are lined with built-in storage and cloth-padded cases where humidity and lighting conditions can be closely monitored. While the rooms are intentionally spare and subdued, the cases are equipped with LED and halogen fixtures that spotlight individual treasures without exposing them to harmful heat.

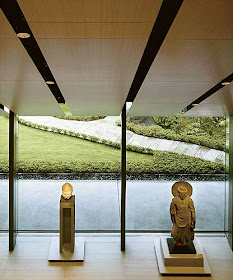

Because earthquakes are a major concern in Japan, stone figures in the sculpture hall stand on pedestals concealing metal springs that absorb seismic tremors. Though the objects are not light sensitive, Kuma carefully coordinated daylight and electrical fixtures to best present the pieces against the backdrop of the newly configured garden. Fanning out from the building, the garden presents a spacious, tree-ringed lawn cut by a path leading to the café. From here, walkways connect to the existing grounds laid out by the Nezu family’s master gardener. Uniting inside and out, a glass wall fronts the sculpture hall. While glass fins securing the wall minimize view-blocking window sashes, oblong, solid-steel columns measuring 4-by-12 inches seem to effortlessly support ceiling beams that enable the room’s 49-foot clear span. Soaring to 49 feet at its apex, the angled ceiling echoes the building’s pitched roof.

The museum’s most distinctive feature—its roof—is a direct quotation from Japanese history but rendered more abstractly, befitting a contemporary museum in an urban setting. While its traditional image ties the museum’s contents and container together, the pitched form, says Kuma, distinguishes the Nezu from the unpopular, boxlike public buildings around the country that do not blend with the Japanese environment. “A pitched roof harmonizes the ground and architecture,” he explains. Charcoal-colored ceramic tiles clad the entire roof surface, and their uniform texture accentuates the angled planes. Instead of ending with the typical, decorative flourish at the ridge or gutter, the matte surfaces terminate in tapered, sharp-edged eaves made of 0.13-inch-thick sheets of industrial grade steel—the same material covering the museum’s exterior walls.

Supported by 9-foot-long, cantilevered beams, the eaves shield the front walkway but submerge it in semidarkness. “People usually expect lighter spaces in public buildings,” comments Kuma. “But this darkness is necessary to separate [the museum] from Omotesando.” Black sandstone pavers compound this shadowy effect, while bamboo walls mitigate it. (Two rows of live bamboo plants buffer the building from the street, and split stalks adorn the facade, forging connections with both the garden and the interior.)

|

| Photo © Courtesy of Shinkenchiku-Sha--The new building brings the museum closer to the street and gives it a higher public profile, while protecting the garden beyond. |

|

| first floor plan--drawing Courtesy of Kengo Kuma & Associates |

|

| second floor plan--drawing Courtesy of Kengo Kuma & Associates |

The PeopleArchitect:Kengo Kuma & Associates 2-24-8 Minamiaoyama Minato-ku 107-0062 Tokyo, Japan TEL: 81-3-3401-7721 FAX: 81-3-3401-7778 Kengo Kuma REGISTERED, Minoru Yokoo, Toshio Yada REGISTERED, Takumi Saikawa, Atsushi Kawanishi REGISTERED, Ryohei Tanaka, Ayumi Motose Engineer(s): Shimizu Corporation Consultant(s) Landscape: Seifu-en Lighting: General Planning: Panasonic Electric Works Co., Ltd. Lighting for Exhibition Kilt Planning Office INC Acoustical: Other: Showcase Designing / Kokuyo Furniture Co., Ltd. General contractor: Shimizu Corporation Photographer: Mitsumasa Fujitsuka phone number 03-5410-9220 CAD system, project management, or other software used: Auto cad | The ProductsStructural system:Steel structure /steel-reinforced concrete structure Exterior cladding Metal/glass curtainwall: Techno Namiken Co. Ltd./ steel panelt3.2 hot dipgalvanizing phosphate finish Roofing Tile/shingles: Marueitogyo Co. Ltd./Japanese clay tile Other: eaves:steel panelt3.2 hot dip galvanizing phosphate finish Glazing Glass: Asahi Glass Co./laminated tempered glass / laminated heat resistance glass Doors Entrances: laminated tempered glass Interior finishes Ceilings: bamboo sliced veneer Wallcoverings: bamboo sliced veneer / sand stone t30 Flooring: sand stone t30 / cork flooring t4.0 Lighting Interior ambient lighting: halogen lamp / fluorescent lamp Task lighting: halogen lamp Exterior: halogen lamp Exhibition lighting : halogen lamp(fiber optic)/ LED lighting Exhibition lighting Controls: Lutron light control system |